Exhibition texts in English

The Poet and the Social Critic Kielland and his Era Kielland and Art Kielland and Europe Kielland and the Truth The letter writer Kielland and the Writing Process Kielland and Nature The Social Critic The Poet and the Town Kielland and the Good Life Freedom of Expression The Literature Wheel Timelines

The Poet and the Social Critic

Nothing is so boundless as the sea, nothing so patient. On its broad back bears, like a good-natured elephant, the tiny mannikins which tread the earth; and in its vast cool depths it has place for all mortal woes. It is not true that the sea is faithless, for it has never promised anything; without claim, without obligation, free, pure, and genuine beats the mighty heart, the last sound one in an ailing world. (From Garman & Worse, 1880)

Just as the sea contains multitudes, Alexander Kielland encompasses a great deal, both as a person and as an author. He wrote about the things closest to his heart, such as nature, small towns, and their residents. At the same time, Kielland is known as a ‘tendency poet’. He addressed the current and political issues of his time and wished to change society through his literature. Kielland was active during the period of literary history known as ‘Realism’, and had a strong ideal of truth that imbued both his life and his writing.

Contradictions

Kielland's life was filled with contradictions. He was born into the upper class and was part of Stavanger’s bourgeoisie – and this privilege influenced his personal consumption throughout his life. At the same time, Kielland the author always stood on the side of the weakest members of society, and this apparent contrast led to an inexorable inner conflict. Kielland also had many roles — lawyer, brickyard owner, writer, journalist, mayor and county governor — but he always longed to write. He had deep roots in Stavanger and Jæren, and this was reflected in his writing. But Kielland also turned his gaze outward, towards Europe. He longed to escape small town life, and he kept up with the major thinkers of his era. Kielland spent time living abroad and elsewhere in Norway – but when he did, he found himself missing Stavanger: “[...] with each passing day, my yearning to return home to Bredevannet increases.” (Letter to his brother Jacob, 1888)

Social Analysis

Kielland’s career as an author was short-lived; after just over a decade of writing, Kielland felt burnt-out. Yet in that time, he managed to write a great deal: plays, novellas, and novels. He also wrote many letters, which were published after his death. Kielland was fascinated by society and people’s interactions, and the sharp social analyses in his work is still recognizable to the modern reader.

Poetic Descriptions of Nature

Kielland is also appreciated for his literary merits, for his poetry and for the distinctive moods of his writing. For example, Sigbjørn Obstfelder writes about the short story Karen: “ – Upon reading such a poem as Karen, one cannot help but proclaim that this prose poetry is more than any verse. And indeed it is — there is music in the words as well as in the thoughts, such a satisfying music — – – – Read it!”

Relevance

Kielland described his literary characters simply, with a few typical traits. Nevertheless, he managed to imbue them with substance, and they inspire feelings of recognition and empathy, even in modern readers. Kielland knew that being human is difficult, and his literature contains something human and nuanced. Despite its apparent indignation, there is warmth and compassion in everything Kielland wrote — an attribute that is perhaps better understood when one considers how difficult it was for Kielland to live up to his own ideal of truth. And perhaps this is also one of the reasons why his literature contains friction and conflicts at several levels.

Kielland and his Era

Kielland can be read with an eye to the era to which he belonged. At the same time, his works bring to life the story of his hometown and provide a snapshot of life in Stavanger at the end of the 19th century.

Stavanger in Kielland’s Time

Kielland was born in 1849, and in the course of his lifetime society went through a series of major upheavals. In the 1860s, when he was a student at Kongsgård School, Stavanger had around 18,000 inhabitants. Although the town was small, it was an important port. Herring fishing, and later the canning industry, employed large portions of the population and also introduced many outside influences. The town had a multitude of international contacts established through trade, seafaring and missionary work. Around the turn of the 20th century, Stavanger acquired a library, museum and theatre, and telephone and telegraph connections were set up in the town.

The Author’s View of Society

Industrialisation, population growth and urbanisation were changing society. New ways of thinking were emerging, and the writings of Kielland are clearly characterised by the trends of the period, including women’s rights, the worker’s movement, and the call for universal suffrage. In keeping with the Realist tradition, he endeavoured to reveal the truth and illuminate societal problems. His writings reflect his ability to listen and observe as he moved among various social strata, and his sharp analyses of his own time period continue to engage modern readers.

Kielland and Art

Kielland came from a family that was passionate about literature, art, and music. The Kielland family home was a natural meeting point where there was room for discussion and conversation about everything from social issues to art.

Music

Music was one of Kielland's great interests. He played the flute, and started a quartet with his friends. We can also find traces of Kielland’s musical interest in many of his writings. In the novella "Siesta" (1880), Kielland intentionally uses references to music and musical performances in the composition of the text.

Alexander and Kitty

The author's sister Kitty is considered to be one of Norway’s most important artists, and was a pioneer of the local genre of painting known as "jærmaleriet" (named after the landscape of the Jæren region). Alexander and Kitty had a close bond and shared their challenges and experiences with each other, often through letters. They spent time living together in Paris, where they had a large shared circle of friends which included writers and artists such as Harriet Backer, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and Jonas Lie. The novella "Torvmyr" ("Peat Bogs on Jæren") is the work that binds Alexander and Kitty together. Kitty created a drawing of the same title, and challenged her brother to write an accompanying text. His response to the invitation was a grotesque, comic and melancholic work. Both the text and the drawing convey the siblings’ concern regarding man-made changes to the landscape and nature, and are inspired by Jæren’s distinctive landscape, of which they were both so fond.

Kielland and Europe

Travel Abroad

For an artist seeking inspiration and new impulses, life in a small town such as Stavanger must have been challenging. Kielland felt compelled to leave his hometown in order to realise his dream of becoming a writer. Thus, in the spring of 1878 he left behind his job, wife, and young children to travel to Paris and write. During his stay in Paris, and later in Copenhagen, he made important contacts. The author visited several European countries and also travelled to the Mediterranean region in connection with a sea voyage. During his time as a county governor in Molde, he was enthusiastic about everything he got to see and experience during his business trips throughout the district.

Impulses from Abroad

“Don't forget to give me frequent hints about the books I should read; at home I sit with a pot over my head, and see and hear nothing”, wrote Kielland to the Danish author and politician Edvard Brandes. The brothers Georg and Edvard Brandes exercised enormous influence on the intellectual and artistic milieu in Scandinavia. They had important and trend-setting contacts throughout Europe, and the flow of thoughts and ideas throughout this network had a major impact on Kielland's authorship.

Through his travels, literature and letters, Kielland brought the world home to Little Stavanger, in the form of thoughts and ideas that took root in his writing.

Alexander Kielland and the Danish author, Jens Peter Jacobsen (1882/1883). Photo: Nasjonalbiblioteket

Kielland and the Truth

Kielland’s authorship is an attempt to reveal the truth through writing.

Realism

Kielland was part of the realist movement that originated in the mid 19th century. Realism was a response to Romanticism, which was permeated by emotional and visionary elements. It reflects the major changes of society that characterised Kielland’s era, and was a kind of continuation of the central ideas about knowledge and progress first disseminated during the Enlightenment. Yet the Realist literary movement is still alive today, for example in the form of the autobiographical tendencies of contemporary literature – so-called ‘hyperrealism’. The starting point of realism is mimesis – imitation – the attempt to describe reality in as detailed and truthful a manner as possible, and recognition is a touchstone of the movement.

Truth

Kielland was heavily influenced by the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, in particular by Kierkegaard's thoughts on truth. In his writing, Kielland constantly grappled with the injustices and social problems of his day. He wished to shed light on these issues and thus reveal the truth. At the instigation of the influential literary critic Georg Brandes and the “the Modern Breakthrough” — the transition to Realism in Scandinavian art and literature — Kielland used his literature to debate social, political, moral and religious views.

The letter writer

Alexander Kielland is renowned as having been a prolific letter writer, and more than 2000 of his letters have been preserved. Kielland described letters as “the sound of a far-away friendship”, and as confidential conversations in written form.

Letters as Literature

The use of letter writing in literature dates all the way back to antiquity, and can be regarded as a literary genre in its own. The letters left behind by Kielland are private, but they also have literary qualities. Throughout his life, he corresponded with family, friends, and business associates, and not least with other authors and artists. He himself saw the letters as part of his authorship. The first collection of his letters was published just one year after his death. Numerous compilations were subsequently published, and the author's letters are now just as popular with readers as his novels and short stories.

Kielland’s Letters as a Source of His Authorship

The letters are personal messages that provide insights into Alexander Kielland – as a man, an author, and a critic. They illustrate his concern for his nearest and dearest, his wit and humour, but also his penchant for melancholy and heavy thoughts. In them, he found an outlet for his despairs about money worries, marital problems, and writer’s block. The letters offer insights into Kielland’s close friendships with numerous authors of his era, as well as his thoughts on literature, writing and key themes in his literary œuvre.

Kielland and the Writing Process

The Urge to Write

Although Kielland is best known as a social critic and Realist, he also found writing to be therapeutic. To August Strindberg, he praised himself happily over the fact that he had the ability to transform his own rage into literature. His urge to write came from a burning desire to express himself through language and text. Kielland was a committed and critical writer who wanted his literature to change society. Contact with other authors and intellectuals was of great importance to Kielland's writing process. Through letters, they exchanged ideas and commented on each other's texts.

The Strategist

Kielland worked as a businessman prior to becoming a writer, and was also an accomplished strategist. Although he wished to change society through literature, he was also interested in sales figures and popularity. In a biography of Charles Dickens, he had read about how the author had deliberately worked to increase his sales figures, for example by giving public readings. Kielland did the same and wrote several of his books with such public readings in mind, and with consideration for how they would be received by a broader audience.

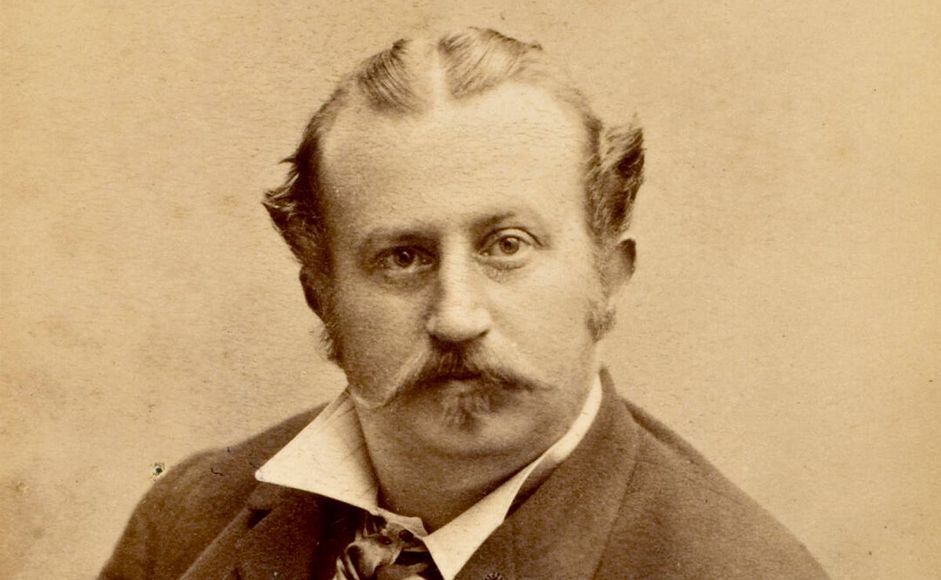

Jacob K. Sømme, Alexander L. Kielland. Photo: Stavanger Museum/MUST

Kielland and Nature

I did not know it before, but after my stay in Paris and since I have started writing, I have come to realise that this coastal landscape, so ugly, so wild, so capriciously despondent, is as dear to me as it is necessary. - Alexander L. Kielland

A Love for Jæren

Kielland's love of nature was inextricably linked to Jæren and his family’s country house at Orre. It also inspired his authorship and stayed with him throughout his life. In Stavanger, he competed with the renowned gardener Poulsson in his efforts to persuade the hyacinths to bloom. He also dedicated himself to protecting the nature and wildlife of Jæren. At Orre, Kielland convince large-scale farmers to preserve their estates, and in 1891 he wrote in a letter about the need for what is now the Norwegian State's Nature Supervision Authority: “Were it not for the unfortunate fact that the Norwegian Parliament has actually voted that I am immoral, I would seek to become a bird inspector in Western Norway. Then I would travel around and teach people about the birds [...].”

Nature in Kielland’s Authorship

Kielland's deep respect for nature and wildlife is also expressed in his letters, novels and short texts. In Garman & Worse (1880), nature is contrasted with the artificial and diseased aspects of culture. And in the writer’s detailed and thorough descriptions of animal behaviour, it is easy to discern the influence of Charles Darwin and his revolutionary thoughts about man and nature. In Mennesker og dyr (People and Animals) (1891), Kielland sides with the animals in a cultural-critical text that is at least as relevant today as it was when he wrote it. It conveys a modern perspective on nature and echoes present-day ideas regarding nature conservation and ecology.

Peder M. Gjemre, "Jærstrand i kuling". Photo: Stavanger Museum/MUST

The Social Critic

My new story is off to the printer’s, and once it’s published I believe I shall hear quite the commotion. - Alexander L. Kielland

Debating the Issues

The desire to debate important social issues was a fundamental principle of the Realist literary movement. The mission of literature was to highlight social problems in order to help create a better society. Literary texts should have a clear message, they should deal with the present, and they should problematise social, political, or moral issues in order to raise the reader’s awareness. The author should be a highly influential figure in the public debate. Important topics included the rights of women and workers, the role of religion in society, sexual morality and universal suffrage. Among Kielland’s Norwegian contemporaries were the authors Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Henrik Ibsen, Jonas Lie, Amalie Skram, Camilla Collett and Arne Garborg.

The Author's Voice

Kielland was conscious of his privileged position in society. He was born into one of Stavanger's wealthiest bourgeois families, but had liberal political leanings. The ideals of Realism and the search for the truth were thus central to Kielland’s work, both as a writer and as the editor of a local newspaper (Stavanger Avis). He wished to act as a mouthpiece for the weakest members of society, and he endeavoured to move and enlighten readers through his writing. But his commitment came at a cost. Kielland’s critical texts made him a controversial and sometimes unpopular figure, and his applications for poetry stipends were not granted by the Norwegian Parliament.

The Poet and the Town

I now know with Certainty, that every longer Stay in Stavanger is a Danger to Life, just as a shorter one is an Encouragement. - Alexander L. Kielland

The Poet and His Hometown

Alexander Kielland was born into one of Stavanger's most powerful and distinguished families, and grew up in ‘Kiellandhuset’, directly adjacent to Kongsgård School. His hometown is central to his authorship, and together with characters clearly inspired by his own family and acquaintances, it is almost its own literary figure in his stories. The town is inhabited by a myriad of characters. Here the reader meets watchmen who wander the streets, factory workers, members of the bourgeoisie, sailors, peasants and merchants.

The anonymous small town described by Kielland is easily recognisable as Stavanger. Kielland's attacks on small town hypocrisy, double standards and social games were both provocative and entertaining. The author used well-known people as blueprints for his characters, and some felt attacked and exposed.

Stavanger Today

The Kielland Centre is located in the heart of the poet’s beloved hometown, which he used as a source of inspiration. Much has changed in Stavanger since Kielland's time, but from the third floor at Sølvberget one can take in a sweeping panorama of the narrow alleys, streets and small white wooden houses that serve as a backdrop for the bustling small town life we encounter in the author’s writings.

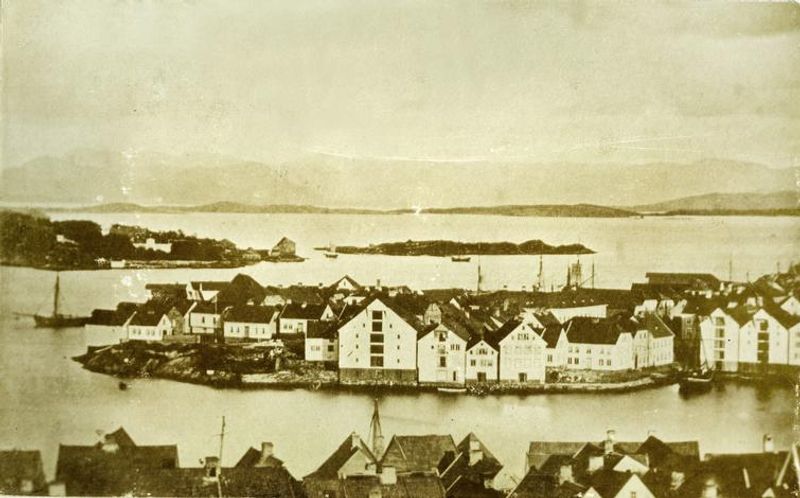

Vågen seen from Blidensol, 1860 Photo: Stavanger byarkiv

Kielland and the Good Life

One continues living, because one believes that champagne and oysters are just around the corner, and because one knows that the sun shines over Aarre Beach. - Alexander L. Kielland

A Lover of Life

Reading Kielland can whet one’s appetite for life – and for food. Despite a lack of money, writer’s block, and other worries, he was a great lover of life. “I'm in a golden mood today, because I've got new clothes from Hamburg – and they fit perfectly!” He knew how to treat himself to a little luxury and liked to stand out from the crowd. Kielland's splendid and sometimes eccentric appearance is often highlighted through imagery and by eyewitnesses. Moderation didn't come naturally for Kielland. He loved food, wine, and women. And although he eventually paid a price for his lifestyle, he had trouble controlling himself. “If I wanted to live like a virgin and nourish myself like a flower, my life could still be long — so they say; but I have no interest in that.”

For Kielland, the good life was also associated with nature and the seaside resort of Orre. The beautiful and wild nature of Jæren was like medicine for him. With his expensive fishing rod from Eaton & Deller in London, he could cast for hours in good company. Few pleasures could compare.

Orre Beach. Photo: Stavanger byarkiv

Freedom of Expression

The purpose of the Kielland Centre is to demonstrate how literature and art can act as social criticism and serve as tools for exercising power and political influence.

Sølvberget is intended as a venue for participation and debate, and houses institutions that can be seen as an extension of Kielland's life and work: The Kapittel Festival for Literature, ICORN (the International Cities of Refuge Network) and Friby Stavanger (Stavanger City of Refuge). Since 1996, Stavanger Municipality and Sølvberget have hosted writers and artists whose work have caused them to be subjected to threats, censorship and persecution, and who have therefore been forced to flee their home.

Freedom of expression is a fundamental value of a democratic society. Norwegian writers can express themselves freely, both in literature and in public debate. Yet in much of the world, free speech is under constant threat, and many writers, artists and journalists are forced into silence and pay a high price for expressing their views.

Freedom of expression is founded on the right to speak out, but also on the right to refrain from doing so. Speech can enlighten and liberate, but it can also provoke and challenge.

The Literature Wheel

What is Realism?

In literary history, the term ‘Realism’ is used for the dominant tendency in literature from around the 1870s to the 1890s. Alexander Kielland is considered one of the foremost representatives of Realism in Norway. Other central Norwegian writers of this era included Camilla Collett, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Jonas Lie and Henrik Ibsen. For these authors, it was important to use literature to address political issues and to illuminate social problems, and they were often regarded as controversial voices in their time. Typical themes within this literary era were the double standards of society, class divisions, religion, and the oppression of women.

The concept of Realism is also applied to fiction that is true to reality. Writing realistically means describing reality as it is. The action of the story and the thoughts and feelings of its characters are depicted in a realistic and credible way.

The Realist Tradition Today

Realism is a literary movement and writing style that is still alive in contemporary literature, particularly in the form of realistic fiction. To varying degrees, many contemporary authors write autobiographically. They often use their own names and the real names of others in their texts, describing events that have actually taken place. Karl Ove Knausgård’s Min kamp (My Struggle) (2009-2011) is one work that represents this tendency.

There are also many examples of realistic contemporary literature that address current social issues, thus “debating the issues”. For example, Olaug Nilssen’s Tung tids tale (A Tale of Terrible Times) (2017) is a clear criticism of the healthcare system. Contemporary climate literature is another example of tendency literature. These types of texts problematise mankind’s relationship with nature and the environment, with an aim to engage and raise the awareness of readers in order to help prevent the occurrence of a future environmental crisis.

What Did Kielland Read?

We know that Alexander Kielland was a well-read man, and that his writing was heavily inspired by the dominant literary currents and tendencies of his era. He read novels, poetry, plays, philosophical texts, newspapers and periodicals. As a young student at the Latin School (Kongsgård School), he read Bible history and the ancient Greek classics, which he later subjected to harsh criticism in the novel Gift (Poison). In it, he argues that the minds of the youth are poisoned by being forced to study old classics, and that they would be better served by learning to think for themselves. As a law student in Oslo, he was an avid user of the university library. He did not limit himself to the books in his syllabus, also exploring the writings of the radical thinkers and philosophers of the time, including John Stuart Mill, Georg Brandes, Søren Kierkegaard, and Charles Darwin.

In the years during which he ran a brickyard in Stavanger and had not yet begun to write, Kielland immersed himself in theology, philosophy, politics, and the arts – and literary history. He read foreign authors such as Shakespeare, Dickens, Strindberg, Flaubert, Balzac, Zola and Heine, but was also keen to familiarise himself with contemporary Norwegian fiction. He was inspired by Camilla Collett, Amalie Skram and Arne Garborg, and of course Ibsen, Bjørnson and Lie. Many of these contemporary writers were friends and acquaintances with whom he socialised and who he encountered on his many trips.

Timelines

Alexander Kielland Timeline

February 18, 1849: Alexander Lange Kielland is born in Stavanger. He was the third of eight children. 1856: Starts studying at the Latin School (Kongsgård School). 1867: Becomes engaged to Beate Ramsland; moves to Christiania (Oslo) to study. 1871: Completes law school and moves home to Stavanger. 1872: Buys Malde Teglverk, a brickyard, and becomes a factory owner. Marries a few months later. 1878: Leaves behind his wife and three small children to go to Paris and write. His desire to become a writer is strong, and Kielland feels he must go away in order to write. 1879: Makes his literary debut with the collection Novelletter (Novellas). 1880: Publishes Garman & Worse, Nye Novelletter (New Novellas), Tre Smaastykker (Three Short Plays) and For scenen (For the Stage). 1881: Publishes Else. En julefortelling (Else – A Christmas Story) and Arbeidsfolk (Working People). Sells the Malde brickyard. Moves to Copenhagen with his family and remains there for almost two years. 1882: Publishes Skipper Worse. 1883: Returns home from Denmark and publishes Gift (Poison). 1884: Publishes Fortuna. 1885: Jonas Lie and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson ask the Norwegian Parliament to grant Kielland a poet’s stipend, but the application is denied. The application is repeated the two following years, but is not granted. 1886: Moves to France with his family. Publishes Sne (Snowfall) and the play Tre Par (Three Couples). 1887: Writes Sankt Hans Fest (Midsummer Party) and Bettys Formynder (Betty's Guardian). 1888: Returns to Stavanger and moves into his childhood home at Breiavatnet. Professoren (The Professor) is published. 1889: Becomes an editor at the Stavanger Avis newspaper. 1891: Becomes mayor of Stavanger, an office he held for nearly 11 years. Publishes Jacob and Mennesker og dyr (People and Animals). 1902: Moves to Molde to become a county governor in Romsdal. 1905: Kielland's last book, Omkring Napoleon (On Napoleon) is published. April 6, 1906: The author dies at Bergen Hospital; his funeral service is held in Stavanger Cathedral on April 11.

Stavanger Timeline

1853: Valbergtårnet is erected as a fire lookout tower for the city's watchmen. 1855: The sailing town of Stavanger gets its first steamship, with a route to and from Ryfylke. 1857: Stavanger gets a telegraph connection. Now short messages can be quickly and easily sent directly to recipients outside of town. 1859: Norway's first temperance league is founded in Stavanger. Alexander Kielland was himself a member of the Temperance Lodge for a few years, but resigned when he and his family moved to France. 1860: The worst fire in several hundred years ravages a huge portion of central Stavanger, leaving close to 2000 inhabitants homeless. 1865: The Stavanger Art Society is founded on the initiative of Jens Zetlitz Kielland, Alexander Kielland’s father. 1873: The town's first canning factory is established. At the time, Stavanger is the country's second largest port. 1877: Stavanger Museum is founded at its first address, Nedre Strandgate 3. 1878: The railway line between Stavanger and Egersund opens, and considerably shortens the travel time to Jæren. 1881: Stavanger gets its first telephone. 1883: The construction of the Stavanger Theatre in Kannik is completed and the curtain rises for the first time with the play Vore Koner (Our Wives). 1885: The town gets its first public library. 1893: The Stavanger Aftenblad newspaper is founded by the priest and leftist Lars Oftedal. 1896: Rosenberg Mek. Verksted, a shipyard, is established. 1899: The Viking football team is established. Football was a new and unknown sport in Stavanger, and the club's first ball was a rugby ball purchased in England. 1900: At the beginning of the new century, Stavanger has less than 30,000 inhabitants. 1905: The Stavanger Kinematograf-Theater opens, and the city thus gets its first cinema. 1906: King Haakon and Queen Maud visit Stavanger on their coronation tour. In a grand procession, they travel by horse-drawn carriage to Ullandhaug and are celebrated with a public party in Bjergsted Park. Kiellandhuset is sold and moved to Eiganes. The house is demolished in 1980.

Genereal Timeline

1849: The Thranian Movement, the first Norwegian labour movement, is established. Among other demands, the movement calls for voting rights for all workers. The first missionaries educated at the Mission School in Stavanger travel to Zululand. 1850: The violinist and composer Ole Bull founds the Det Norske Theater (The Norwegian Theatre, now The National Stage) in Bergen. 1853: Based on his dialect surveys, Ivar Aasen lays out his proposal for a writing standard for a national language. 1854: The first volume of Camilla Collett’s Amtmandens Døtre is published. The novel is regarded as an important contribution to the women’s liberation debate. 1855: Søren Kierkegaard dies. Kielland was later heavily influenced by his thoughts of existentialism and man's search for truth. 1857: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson makes his breakthrough with the novel Synnøve Solbakken. 1858: Aasmund Olavsson Vinje founds the weekly newspaper Dølen. He uses Ivar Aasen's national language and allows the newspaper to act as a mouthpiece for the peasant population in order to secure the ‘silent majority’ a public voice. 1859: Charles Darwin publishes his study On the Origin of Species. 1867: Karl Marx publishes his main work, Das Kapital. 1871: Georg Brandes lectures on the primary currents of 19th century literature at the University of Copenhagen. He argues that the mission of literature is to ‘debate the issues’ and present life as it truly is. 1874: Henrik Ibsen asks Edvard Grieg to compose the music for Peer Gynt. The Norwegian Parliament grants Jonas Lie an artist's salary. 1876: Alexander Graham Bell receives the world's first phone call. 1879: Kitty Kielland debuts at the Salon in Paris with two paintings from Jæren. Henrik Ibsen has his international breakthrough with Et dukkehjem (A Doll’s House). 1882: In the course of a year, a full 28,000 Norwegians move to the United States. Alexander Kielland also considered emigrating at one point, to start a new life for himself and his family. Sigrid Undset is born. 1884: The Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights is founded. Kitty Kielland is one of its initiators, and Camilla Collett is honoured with an honorary membership. In the Norwegian Parliament, the opposition wins a long-standing power struggle against the king and the government. This struggle changed the political system in Norway and is considered the breakthrough for parliamentarianism in the country. 1885: Amalie Skram publishes her first novel, Constance Ring, which contains provocative ideas about marriage and sexual morality. Hans Jæger publishes the controversial Fra Kristiania-Bohemen (From Kristiania-Bohemen). The author's radical views provoke both the bourgeoisie and the government, and all copies of the book are immediately seized. 1886: Arne Garborg publishes Mandfolk (Menfolk), which is considered one of the first naturalistic Norwegian novels. His radical views made him a controversial writer in his time. Through his novel Albertine and the painting Albertine in the Police Doctor’s Waiting Room), Christian Krohg demonstrates the idea that art's task is to depict contemporary problems as truthfully as possible. 1889: The Folk School Act ensures all Norwegian children the right to attend school. Friedrich Nietzsche asserts that God is dead. The Eiffel Tower is inaugurated in conjunction with the Exposition Universelle world’s fair in Paris. 1890: Knut Hamsun publishes Sult (Hunger), a pioneering work of European Modernism, and in his lecture “Fra det ubevisste sjeleliv” (“From the Unconscious Life of the Soul”), he takes a powerful stand against the stylistic ideals of Realism. 1893: Edvard Munch paints his most famous work, Skrik (The Scream). The same year, Sigbjørn Obstfelder makes his debut with the collection Digte (Poems). Both are regarded as examples of early Modernism in Norway. 1895: The Lumière brothers demonstrate the world's first film projector in Paris. 1900: Sigmund Freud develops psychoanalysis. The Stavanger artist Frida Hansen enjoys great international acclaim for her tapestries at the Paris Exposition. 1903: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Kielland's close friend, receives the Nobel Prize in Literature. 1905: Albert Einstein launches the theory of relativity. Dissolution of the Union between Norway and Sweden.